News

Research / 06.02.2026

Leif Si-Hun Ludwig awarded professorship

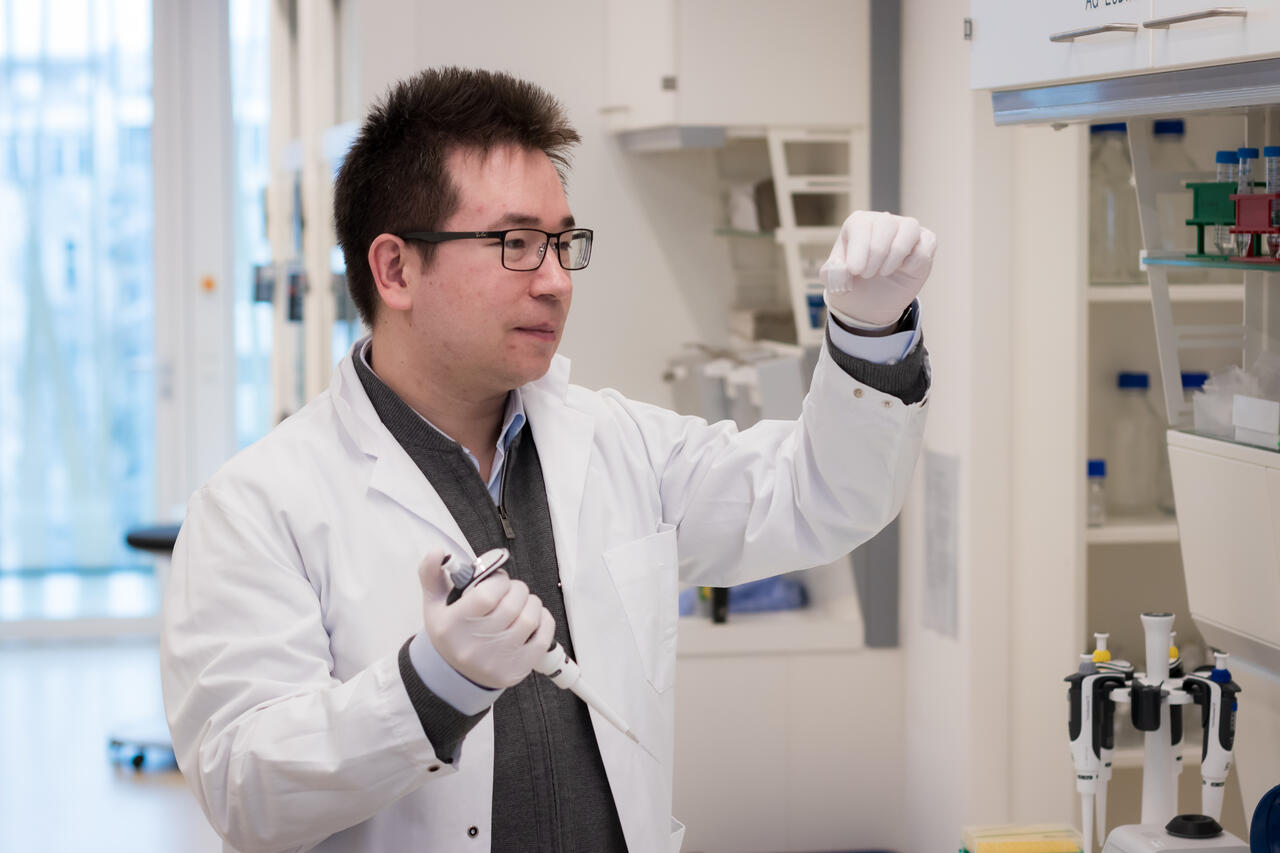

Leif Si-Hun Ludwig has been awarded a prestigious Heisenberg professorship in stem cell dynamics and mitochondrial genomics by the the Berlin Institute of Health at Charité, a position funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG).

Professor Leif Si-Hun Ludwig has led an Emmy Noether Research Group at the Berlin Institute of Health and the Max Delbrück Center since 2020. He has now been awarded a Heisenberg Professorship for Stem Cell Dynamics and Mitochondrial Genomics by the the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) at Charité, a position funded by the German Research Foundation. Ludwig’s professorship will transition into a permanent role following an initial five-year funding period.

Studying how blood cells form

The human blood system is a marvel of constant regeneration, with millions of new cells replacing old blood and immune cells every second. These cells originate from hematopoietic (or blood-forming) stem cells in the bone marrow, maturing through several different developmental stages into the red and white blood cells, platelets, and B and T cells that keep us alive. While clinical blood tests can easily count these cells, determining the specific contribution of thousands of individual stem cells to overall blood production remains a significant challenge.

By observing natural mutations in human DNA, researchers can gain fundamental insights into how stem cells maintain healthy blood formation or how they behave when disease strikes. However, hunting for a single mutation within a genome of three billion base pairs is expensive, time-consuming and prone to error, even with today’s most advanced technology.

Cellular power plants reveal the origin of blood cells

To bypass these hurdles, Ludwig focuses on natural mutations within the mitochondrial genome – a much smaller, more manageable DNA molecule found within cellular power plants known as mitochondria. By pairing this approach with sophisticated single-cell sequencing technologies, his team can analyze tens of thousands of blood and bone marrow cells simultaneously, effectively mapping the activity of blood-forming stem cells. This single-cell analysis of natural genetic variation does more than track lineage; it provides vital information on the health of individual cells. In a clinical setting, this could eventually help doctors to predict the success of stem cell transplants or fine-tune cell and gene therapies with unprecedented precision.

Beyond this work on hematopoietic stem cells, Ludwig is tackling the challenge of inherited mitochondrial mutations. These defects are among the most common genetic disorders and can trigger a wide range of metabolic diseases affecting multiple organ systems. Despite their prevalence, the molecular causes of these conditions remain poorly understood. By investigating how mitochondrial gene variants influence different cellular and metabolic phenotypes, Ludwig aims to lay the groundwork for new therapeutic approaches.

“The Heisenberg program supports outstanding scientists, so it was no surprise to us that Ludwig was selected for this honor,” says Prof. Christopher Baum, Chair of the BIH Board of Directors and Chief Translational Research Officer of Charité. “His exceptional work combines basic research and application-oriented studies. Ludwig and his team are thus strengthening the translational network that brings together the BIH, Charité, and the Max Delbrück Center for the benefit of patients.”

Research / 06.02.2026

Professorship awarded to Mina Gouti

Mina Gouti has been awarded a professorship at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. The appointment will strengthen her pioneering organoid research at the Max Delbrück Center and deepen collaboration with clinicians to advance personalized medicine.

Dr. Mina Gouti, Group Leader of the Stem Cell Modeling of Development and Disease lab at the Max Delbrück Center, has been appointed W3 Professor of Complex Organoid Models for Personalized Medicine in the Medical Faculty, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. The permanent position recognizes her achievements in developing advanced organoid systems to understand how specific types of spinal cord neurons and skeletal muscle cells grow in space and time during development.

“This professorship will enable my team to fully leverage Berlin’s exceptional biomedical ecosystem and to work closely with clinicians at Charité to create complex organoids for personalized medicine,” Gouti says. This close interaction is essential for translating patient-derived organoid models into clinically relevant insights.”

The Gouti lab has developed three-dimensional neuromuscular organoids from human pluripotent stem cells that replicate key features of spinal cord neurons and skeletal muscle – providing powerful platforms for studying neuromuscular diseases such as spinal muscular atrophy and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and for drug screening. Such organoids can also be grown from cells derived from individual patients to model their specific disease.

The position reflects a shared vision between the Max Delbrück Center and Charité to accelerate translational research through fostering closer collaboration between clinicians researchers. “We now have the long-term perspective required to develop complex, functional organoids as predictive platforms for personalized medicine and early disease interception,” says Gouti. “We hope our research will lead to better health outcomes not only for people with neuromuscular diseases, but also those at high risk of developing them.”

Text: Gunjan Sinha

Further information

Research, Innovation / 05.02.2026

Pentixapharm publishes positive Phase II data on Pentixafor PET diagnostics

The study confirms PENTIXAFOR-PET as a non-invasive alternative to adrenal vein catheterization in primary aldosteronism

-

In the study, [68Ga]Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT was well tolerated and demonstrated high specificity and moderate sensitivity for identifying unilateral aldosterone-producing adenomas compared with adrenal vein sampling (AVS) and surgical outcomes

-

The data strengthens the clinical foundation for Phase 3 development and support the role of molecular imaging in guiding treatment decisions in the population with hypertension and underlying primary aldosteronism

Pentixapharm Holding AG (Frankfurt Prime Standard: PTP), an advanced clinical-stage biotech developing novel radiopharmaceuticals, today announced publication of new Phase 2 clinical data in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine demonstrating the potential of [68Ga]Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT as a non-invasive imaging tool for subtyping primary aldosteronism (PA), the leading endocrine cause of hypertension.

The investigator-initiated study, funded by an Australian philanthropic foundation, the CASS Foundation, and the Medical Research Future Fund, was conducted as a prospective cohort study in Australia. It evaluated [68Ga]Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT as a potential alternative to adrenal vein sampling (AVS), the current standard of care for distinguishing unilateral aldosterone-producing adrenal adenomas from bilateral disease. AVS is invasive, resource-intensive, and available only in highly specialized centers, creating barriers to timely and accurate patient stratification.

Results published online show that [68Ga]Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT demonstrated high specificity and moderate sensitivity for identifying unilateral aldosterone-producing adenomas when compared with AVS and surgical outcomes. Importantly, the imaging approach was well tolerated and strongly preferred by patients, with 28 of 29 participants indicating PET/CT as the favoured diagnostic test.

“These data provide evidence that molecular imaging with [68Ga]Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT can support accurate and patient-friendly subtyping of primary aldosteronism,” said Dr. Elisabeth Ng, of the Hudson Institute of Medical Research and the Endocrinology Unit at Monash Health, the lead investigator of the study. “The high specificity observed is particularly relevant for identifying patients who may benefit from curative surgery, while the strong patient preference for PET/CT highlights the potential to expand access to and acceptance of diagnostic testing for patients with primary aldosteronism.”

The study recruited adults with primary aldosteronism and an adrenal adenoma visible on CT imaging. Diagnostic performance was assessed by comparing PET-derived lateralisation indices with AVS results and biochemical outcomes following adrenalectomy. The findings support the clinical utility of [68Ga]Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT as a noninvasive decision-support tool for identifying patients who may benefit from curative surgery.

“This published data builds on earlier investigator-initiated studies, including the CASTUS Step 1 trial and demonstrates reproducible performance across independent studies and geographies. Together, these data strengthen the clinical foundation of Pentixapharm’s primary aldosteronism program and support readiness for Phase 3 development,” said Dirk Pleimes, CEO and CMO of Pentixapharm. “Here, at Pentixapharm, we are continuing to advance our clinical and regulatory strategy for primary aldosteronism while engaging with investigators, regulators, and potential partners to maximise the clinical and commercial impact of our molecular imaging platform.”

As new therapeutic options, including aldosterone synthase inhibitors, are expected to enter the treatment resistant hypertension market, accurate and scalable subtyping of primary aldosteronism is becoming increasingly important. Noninvasive imaging solutions may play a critical role in guiding treatment decisions and optimising patient outcomes in this evolving therapeutic landscape.

The full article, titled “Identification of Aldosterone-Producing Adrenal Adenomas Using [68Ga]Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT in an Australian Cohort,” is available in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

About 68Ga-PentixaFor in treatment-resistant hypertension and primary aldosteronism

[68Ga]Ga-PentixaFor is a novel gallium-68-labeled radiodiagnostic designed to selectively target and visualize the chemokine receptor CXCR4 using high-resolution PET/CT imaging. Clinical experience with [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-PentixaFor PET/CT in approximately 1,600 patients across different indications has demonstrated its ability to non-invasively image CXCR4 expression in vivo.

Recent research has shown strong CXCR4 overexpression in aldosterone-producing adrenal tumors, a hallmark of unilateral primary aldosteronism. Primary aldosteronism is a common but historically underdiagnosed cause of secondary hypertension, largely because reliably distinguishing unilateral from bilateral disease remains challenging with current diagnostic tools. Unilateral disease is typically treated by surgical removal of the affected adrenal gland whereas bilateral disease requires life-long medical therapy. By visualizing CXCR4 expression in aldosterone-producing tissue, [⁶⁸Ga]Ga-PentixaFor has the potential to support more reliable subtyping of primary aldosteronism and thereby better guide appropriate treatment decisions.

About the prospective phase 2 pilot study

The prospective pilot study recruited adults with PA and an adrenal adenoma visible on CT and evaluated 68Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT as a noninvasive nuclear imaging alternative to AVS, assessing its diagnostic accuracy and acceptability compared with AVS in a multiethnic population. PentixaFor was supplied by Pentixapharm AG. The study was published in the Journal of Nuclear Medicine (JNM), which is a top-ranked peer-reviewed publication covering molecular imaging, PET/CT, and theranostics [Ng E, Jong I, Lau KK, Akram M, Morgan J, Nelva P, Simpson I, Haskali MB, Fuller PJ, Shen J, Yang J. Identification of Aldosterone-Producing Adrenal Adenomas Using [68Ga]Ga-Pentixafor PET/CT in an Australian Cohort. J Nucl Med. 2026 Jan 29:jnumed.125.271006. (doi: 10.2967/jnumed.125.271006. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 41611475].

About Pentixapharm

Pentixapharm is an advanced clinical-stage biotech expanding the boundaries of radiopharmaceuticals. Headquartered in Berlin, Germany, the company develops precision diagnostics and therapeutics in oncology and cardiology to transform patient care. Its clinical pipeline is anchored by CXCR4-targeted PET-CT programs, including a Phase 3-ready candidate for the improved diagnosis of hypertensive patients with primary aldosteronism, which is intended to enable targeted treatment of the underlying causes of hypertension. CXCR4-based developments also include pioneering therapeutic programs in hematological cancers. Furthermore, Pentixapharm is advancing a next-generation antibody platform targeting CD24, an emerging immune-checkpoint marker over-expressed in multiple hard-to-treat cancers. Complemented by CXCR4 and CD24 intellectual property protection and a reliable isotope supply chain, Pentixapharm is poised to deliver meaningful patient benefit and sustainable growth in one of the fastest-growing areas of precision medicine.

Innovation / 29.01.2026

Eckert & Ziegler on Track as Planned and Achieves Another Record Year in 2025

Fiscal Year 2025 (preliminary):

- Sales: approx. € 312 million (PY: € 295.8 million)

- EBIT before special items: approx. € 78 million (PY: € 65.9 million)

- Net income: approx. € 48 million (PY: € 33.3 million)

According to preliminary, unaudited figures for the 2025 financial year, Eckert & Ziegler SE (ISIN DE0005659700, TecDAX) generated sales of around € 312 million and adjusted EBIT of around € 78 million. Sales are up around 5% on the previous year, while adjusted EBIT is up by around 18%. Net profit (from continuing and discontinued operations), which is only reported here for comparison purposes, rose to around € 48 million (previous year: € 33.3 million).

The forecast for the 2026 financial year will be published on 26 March 2026 together with the complete, audited annual financial statements for the 2025 financial year.

About Eckert & Ziegler.

Eckert & Ziegler SE with more than 1.000 employees is a leading specialist for isotope-related components in nuclear medicine and radiation therapy. The company offers a broad range of services and products for the radiopharmaceutical industry, from early development work to contract manufacturing and distribution. Eckert & Ziegler shares (ISIN DE0005659700) are listed in the TecDAX index of Deutsche Börse.

Contributing to saving lives.

economic development / 29.01.2026

OMEICOS Therapeutics Announces Positive Phase 2 Study Outcome Demonstrating OMT-28’s Potential in Primary Mitochondrial Diseases (PMD)

Trial Results Support Transition into Late-Stage Development with Program Expected to be Phase 2b/3-ready in H2 2026

OMEICOS, a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company developing first-in-class small molecule therapeutics for mitochondrial and inflammatory disorders, announced the successful conclusion of its multi-centre, open-label Phase 2a PMD-OPTION Study evaluating its lead program OMT-28 in patients with Primary Mitochondrial Disease (PMD). The study results demonstrate OMT-28’s therapeutic potential to improve the physical condition in PMD based on significant recovery of the impaired mitochondrial fitness in the responding patients. The study further underscored the excellent safety and tolerability profile of OMT-28, which has now been evaluated in more than 220 individuals. OMEICOS is preparing for a potentially pivotal Phase 2b/3 study in PMD patients with myopathy and/or cardiomyopathy across EU and US sites and expects to be ready to initiate this study later this year, subject to the completion of partnering discussions.

PMD represents a heterogeneous group of conditions including the more prevalent subtypes MELAS, non-MELAS, and MIDD. PMD patients suffer from debilitating and life-threatening health consequences, such as severely limited physical stamina and disease-related changes in the heart and skeletal muscles, as well as associated neurological disorders. OMT-28, an orally available biased modulator, targets the GPCR-receptor S1PR1 (Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Receptor 1 thereby driving downstream activation of the mitochondrial sirtuin family members SIRT1 and SIRT3. By targeting S1PR1 and activating SIRT1/SIRT3, OMT-28 combines immunomodulation with mitochondrial protection—a dual mechanism to tackle inflammation and energy deficits in primary mitochondrial diseases.

“Improving physical performance through enhanced mitochondrial metabolism and reduced oxidative stress holds great promise in PMD. Our PMD-OPTION study results indicate a strong correlation between OMT-28 treatment, the observed positive impact on mitochondrial bioenergetics and fitness, and relevant clinical improvements in functional measures, which could translate into significant patient benefit,” said Dr. Robert Fischer, CEO/CSO of OMEICOS Therapeutics. “The profound effects on NAD⁺ and GSH levels, as well as simultaneous improvement of the NAD⁺/NADH and GSH/GSSG ratios we have seen in the responder group, are integrative indicators of electron transport chain function improvements and cellular redox homeostasis. Overall, the results offer a robust path for late-stage development.”

Study Design and Results Summary

The PMD-OPTION study enrolled a total of 29 PMD patients with mitochondrial tRNA point mutations or single mtDNA deletions across nine expert sites in Germany, Italy, and The Netherlands. The study generated strong interest among patients and key opinion leaders (KOLs), resulting in timely recruitment and a high degree of compliance with the study protocol and follow-up appointments. The study included a 12-week untreated run-in phase as an integrated control, capturing the patients’ natural history and baseline parameters for evaluating treatment results. Subsequently, all patients received a 24 mg once-daily dose of OMT-28 for a treatment period of up to 24 weeks. The study ended after a subsequent four-week follow-up period. The level of GDF-15, a prospective biomarker for reflecting cellular stress and inflammation, was used as a screening and inclusion criteria, while reduction of GDF-15 was used as a primary endpoint next to demonstrating safety and tolerability in PMD patients. The study outcome did not support the choice of GDF-15 in this setting suggesting that OMT-28 is acting downstream of the release mechanism of GDF-15.

To assess clinically meaningful improvements in the study population, the PMD-OPTION study utilized a combination of objective exercise endpoints and patient-reported outcomes. Using these measures, the study demonstrated a response rate of more than 60%. In the 12-Minute Walk Test (12 MWT) and the 5x Sit-to-Stand Test (5xSST), both accepted endpoints for pivotal studies, the entire study population showed improvements over baseline, while OMT-28 responders exhibited profound and statistically significant (12 MWT) clinical improvements compared to non-responders.

These results strongly correlated with a highly significant increase in total NAD+ levels in the responder group compared to baseline, and a clear separation between responders and non-responders in NAD+/NADH ratios over the course of the study. In patients responding to OMT-28 treatment, mean NAD+ levels were approximately 30% higher compared to baseline, bringing this crucial indicator of mitochondrial energy metabolism and redox status close to healthy ranges. Similarly, OMT-28 demonstrated a significant improvement in total GSH and GSH/GSSG ratios—key indicators of reduced oxidative stress in mitochondrial diseases—thereby reestablishing normal, healthy levels and even showing a trend toward further enhancement. Together, these results demonstrate that OMT-28’s ability to normalize both NAD⁺/NADH and GSH/GSSG ratios addresses the core pathologies of PMD—energy deficiency and oxidative stress—differentiating it from single-mechanism approaches and supporting its potential as a first-in-class therapy.

About OMEICOS

OMEICOS Therapeutics has discovered a series of metabolically robust synthetic analogues of omega-3 fatty acid-derived epoxyeicosanoids that have the potential to treat mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammatory, cardiovascular and other diseases. Epoxyeicosanoids activate cell type-specific endogenous pathways that promote organ and tissue protection. OMEICOS’ small molecules are orally available and show improved biological activity and pharmacokinetic properties compared to their natural counterparts. For more, please visit: www.omeicos.com

Innovation / 14.01.2026

A fresh take on proteomics

Start-up company Absea Biotechnology GmbH is developing new proteomics technologies. An interview with Dr. Philip Lössl, Senior VP Science and Business Development

What makes the Absea Biotechnology Group special?

Absea Biotechnology develops protein science technologies to advance proteomics. One of our main areas of focus is developing monoclonal antibodies for the entire human proteome. These antibodies can detect highly specific molecular biomarkers or diseased cells, such as those associated with cancer or autoimmune diseases. In collaboration with our sister companies in China and the U.S., we have amassed the world’s largest library of recombinant human proteins, which we are continually expanding through our high-throughput protein production platform. Alongside this, we are establishing mass spectrometry pipelines in Berlin to better understand protein–drug interactions (PDIs).

We see ourselves as partners and service providers in proteomics, in vitro diagnostics, and pharmaceutical and life sciences research.

How did the Absea Biotechnology Group come about?

Immunology professor Wei Zhang laid the groundwork. While earning her Ph.D. at Cambridge, she collaborated with Nobel Prize winners César Milstein and Gregory Winter, who studied the fundamentals of monoclonal antibodies. After founding her first antibody company, Zhang worked closely with the Human Protein Atlas project. Absea later developed an even larger partnership with Olink, a Swedish company that is now part of ThermoFisher. Since then, Absea has developed thousands of protein antigens and monoclonal antibodies for Olink. In 2020, the Absea Group was reorganized around bioinformatician Tao Chen to better support this proteome-wide approach. In 2023, we established our Berlin-based start-up, focusing on mass spectrometry research and development.

What is the secret behind Absea’s extensive protein library?

Tao Chen developed a machine learning-based algorithm for designing protein constructs. These constructs correspond to natural sequences found in our bodies, though they are sometimes slightly shorter. Thanks to the algorithm, we know exactly how to shorten the proteins in order to produce them efficiently and cost-effectively with a high success rate.

What innovations are you pursuing?

Our antibody and protein libraries map the proteome and support affinity-based methods. This treasure trove of molecules can also help us develop more unique mass spectrometry technologies and complement “making molecules” with “mapping molecules.” Our scientific advisors, Mikhail Savitski from the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg and Fan Liu from the Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP), both leading experts in mass spectrometry proteomics, encouraged us in this endeavor. Together with Matthias Mann– Germany’s most cited researcher, one of the founding fathers of proteomics, and a researcher at the Max Planck Institute of Biochemistry (MPIB) in Martinsried – we published an approach to using our proteins for clinical testing mass spectrometry.

What does this approach entail?

Proteomics typically only allows for the relative quantification of protein biomarkers: a physician could tell you that you have more of a certain protein in your blood than last time, but they could not tell you the exact amount. Therefore, absolute quantification of biomarkers is important for clinical diagnostics. Until now, peptides labeled with heavy isotopes have been used for this purpose. However, this method only allows the part of the protein biomarker covered by the peptide to be seen and quantified. For this reason, we started producing whole proteins labeled with isotopes. Until now, this was not possible on a large scale. Thanks to our many years of experience in protein production, however, we have figured out how to do this.

When these labeled proteins are added to the sample, they are much more similar to the biomarker because both are proteins. Unlike peptides, proteins can be included in sample preparation. This enables researchers to monitor where deviations occur. During sample preparation, the biomarker and the labeled protein are broken down into peptides. The isotope-labeled counterpart is also found in the peptides. This provides a large number of data points for quantifying the biomarker. If the correlation with the labeled counterpart is incorrect, further mass spectrometry measurements can determine what happened in this region.

This allows parallel and highly sensitive testing of entire protein panels for a specific disease to detect abnormal quantities. At this level, the results could be relevant to clinical practice.

A path to clinical application would therefore be possible.

That is our hope. The plasma proteomics community is proposing the same approach. We are already working with a European university hospital, but we are still in the research and development phase.

However, we have even more plans: we are developing a methodology platform to better map protein–protein and protein–drug interactions at the molecular level. Our goal is to analyze these interactions directly in intact cells, tissue lysates, and cell lysates to gain a better understanding of diseases and the effects of drugs. Ultimately, we want to help our partners develop more effective drugs.

How would you go about doing that?

The first step is to determine if a drug binds to the intended protein and if there are any other unexpected – or even undesirable – binding partners. We use mass spectrometry technology to accomplish this. This technology can show us which protein areas are blocked by a drug across the entire proteome. We also discover the precise location where the drug binds. This information tells us, for example, whether the drug can inactivate the protein or prevent it from interacting with other proteins.

The second step involves protein-protein interactions (PPIs). Which PPIs occur in treated or untreated cells? Which ones occur in healthy or diseased cells? Crosslinking mass spectrometry provides an overview of the entire cellular network. Using our antibody libraries, we can then go into greater depth: we can use crosslinking to fix all protein–protein contacts in the cell. Then, the protein of interest can be enriched using one of our numerous antibodies and extracted from the cell with all its interaction partners for analysis.

Which customers are you targeting with this approach?

For pharmaceutical customers, we can identify disease-relevant protein targets for drugs in the early stages of development. By showing exactly how drugs work, we can determine which candidates are worth further development.

Another customer group consists of protein biotechnology companies that specialize in AI. Our comprehensive, high-quality datasets contain thousands of PPIs and PDIs, providing these companies with valuable information for developing their AI models.

Starting in January, your start-up will be located in the BerlinBioCube incubator

We look forward to being in the same building as the other start-ups, exchanging ideas and supporting each other. I believe this is an ideal ecosystem for us to grow in. We already have academic collaborations on campus with the FMP and the Max Delbrück Center. We also have strong relationships with biotech companies. We see a lot of potential for joint projects at this location.

The interview first appeared in Standortjournal buchinside 1/2026.

Research / 09.01.2026

A double-pronged attack on malignant B cells

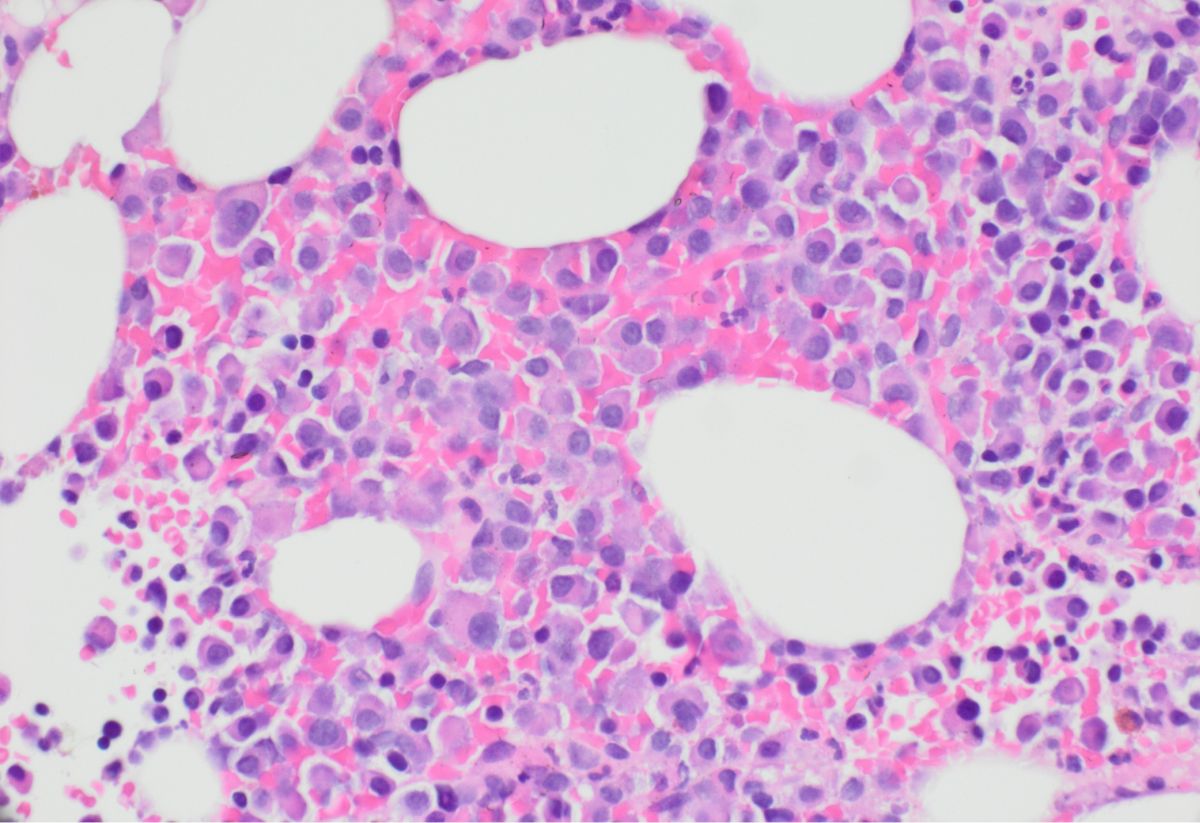

Multiple myeloma, a cancer of the bone marrow, remains difficult to treat despite modern CAR T cell therapies. In “Molecular Therapy,” a team led by Armin Rehm presents an improved immunotherapy that recognizes two distinct features of malignant cells to destroy the cancer more effectively.

Multiple myeloma is a devastating diagnosis. The disease usually develops in the bone marrow where mature B cells called plasma cells begin to proliferate uncontrollably and produce excessive amounts of antibodies, some of which are defective. The cancer, which destroys bone and other tissues, can become extremely painful. To date, it remains uncurable.

In recent years, modern CAR T cell therapies have significantly extended the lives of many myeloma patients, but their effectiveness has been limited. “In some patients, the treatment does not work at all. In others, relapse occurs sooner or later, which then often rapidly leads to death,” explains Dr. Armin Rehm, Group Leader of the Translational Tumorimmunology lab at the Max Delbrück Center.

In the journal “Molecular Therapy,” the Berlin-based researcher, Dr. Uta Elisabeth Höpken, also at the Max Delbrück Center, and an international team present an optimized immunotherapy: CAR T cells that bind to two receptors simultaneously to destroy cancer cells instead of just one, as was previously the case.

Not all patients express the BCMA receptor

Before the advent of CAR T cell therapy, multiple myeloma was treated with chemotherapy and antibody-based drugs, and sometimes combined with autologous stem cell transplants. These approaches, however, were not curative either. CAR T-cell therapies gave patients new hope.

The treatment involves collecting T cells from patients and genetically engineering them in a bioreactor to express a chimeric antigen receptor, or CAR. These receptors act as sensors that help immune cells detect specific surface proteins. In the case of multiple myeloma, the target is BCMA, a protein found almost exclusively on plasma cells, and not on normal B cells. The modified T cells are then reinfused into patients, where they seek out and destroy cancer cells in the body.

“However, BCMA protein isn’t present on all malignant plasma cells,” says Rehm. In some patients with multiple myeloma, it’s not detectable at all; in others, it disappears over the course of treatment. “That’s why we combined three methods – single-cell RNA sequencing, immunohistochemistry, and flow cytometry – to search for another surface marker characteristic of malignant B cells. That led us to BAFF-R,” says Dr. Agnese Fiori, the study’s first author and a member of Rehm’s team, who now conducts research at Charité- Universitätsmedizin Berlin.

Prevention and treatment of relapse

Two additional researchers also made significant contributions to the study: Professor Jörg Westermann, Deputy Clinic Director and Head of Hematological Diagnostics at Charité, and Professor Jan Krönke, Head of the Department of Internal Medicine C – Hematology, Oncology, Stem Cell Transplantation, and Palliative Medicine at Greifswald University Medical School.

“BAFF-R is particularly abundant on cells from multiple myeloma patients who have relapsed,” says Fiori. In addition, it is often found on abnormal plasma cells without BCMA, which are resistant to conventional treatments. “Therapeutically, it therefore makes sense in two respects to use CAR-T cells that recognize both BCMA and BAFF-R,” explains Rehm.

Around 5 to 30 percent of all patients with multiple myeloma could benefit from this dual approach, adds Rehm. For personalized therapy, it is crucial to identify these patients using an appropriate test before treatment begins, he explains. Such screening would be easy to implement in clinical practice.

Success in experiments with cancer cells

Rehm and his colleagues have tested the bispecific CAR T cells both in multiple myeloma cell lines and in patient-derived bone marrow cells. “In all of our experiments, we showed that the improved CAR T cells remain effective, even when the BCMA receptor is absent or has been lost due to therapy – that is, even when treatment with monospecific CAR T cells has failed,” he explains. He hopes that the new approach can prevent relapse in many patients and also extend lifespan – perhaps even offer a cure.

“To truly assess the potential of our method, an initial clinical trial is now necessary,” Rehm adds. Together with colleagues from the National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) – a long-term collaboration between the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ), excellent partners in university medicine, and other outstanding research partners at various locations in Germany, including the Max Delbrück Center, Charité, and the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) as partner sites in Berlin – he plans to apply for the requisite funding. He hopes patients may soon be able to benefit from the optimized CAR T cells.

Text: Anke Brodmerkel

www.mdc-berlin.deResearch / 08.01.2026

A new opportunity for Berlin

The Einstein Center for Early Disease Interception has been funded with six million euros. In an interview, Nikolaus Rajewsky and Leif Erik Sander, both spokespeople of the center, explain why new technologies and cross-institutional collaboration will make disease prevention in the future possible.

The phrase “early disease interception” is included in the Einstein Center’s name. What does that mean in concrete terms?

Professor Nikolaus Rajewsky: Pathological processes in tissues often progress for years unnoticed before symptoms appear. By that point, the damage is usually substantial and can only be reversed to a limited extent. It would be far better to intervene much earlier at a stage when only individual cells are affected and when we can better influence the disease trajectory.

Thanks to major technological advances, we now effectively have a molecular super microscope. We can make disease processes visible at subcellular resolution – in tissues, in body fluids, even in the air we exhale. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are helping us to manage the enormous volumes of data generated from our research and predict disease trajectories.

We want to understand the earliest mechanisms that drive cells away from a healthy equilibrium toward disease and to control which path these cells take – that is what we mean by “interception.” We can now realistically test such targeted interventions before damage occurs, for example using organoids, which are miniaturized models of organs.

Professor Sander, how would you explain this approach to your patients?

Professor Leif Erik Sander: At its core, our approach is about very precise prevention. What matters to patients is that their quality of life and organ function are preserved – even if pathological changes have already begun at the cellular level.

In cancer screening, such approaches already exist, albeit using more conventional methods. For many other diseases, however, we currently intervene too late. When dementia is diagnosed, for example, we can only slow progression of the disease. A similar situation exists with certain lung diseases that can cause progressive tissue scarring, which can lead to death.

Conventional methods cannot detect the early warning signs of such diseases – and we do not always understand what is actually going wrong or how to intervene. This is where early disease interception comes in: we want to understand what knocks the system off course, and create opportunities to reset it at very early stages. The train should, so to speak, be put back on a healthy track.

How exactly does this super-microscope work?

Nikolaus Rajewsky: Today we can analyze very precisely at what point in time, which cells in a tissue access which information in their genome – or do not. A single histological section contains around 100,000 cells, each with about 20,000 genes. Accordingly, the resulting data volumes are enormous. Based on these data, we can reconstruct disease-relevant signaling pathways and complex metabolic networks. The decisive advance is that we no longer merely describe disease, but understand it causally. This is the prerequisite for targeted and early intervention.

What are the biggest hurdles on the path to clinical application?

Leif Erik Sander: These extremely high-resolution methods provide exactly the information we need to distinguish early disease processes. Right now, they are research tools and are very expensive. The crucial next step will be to greatly reduce the complexity and to develop robust, simplified tests that are suitable for large numbers of people.

Artificial intelligence will play a key role. We want to use it to link molecular data with routine clinical data, identify patterns, and specifically predict individual disease risks.

The Einstein Center will be funded for six years. What do you expect to achieve during this time?

Nikolaus Rajewsky: What is emerging here in Berlin goes beyond individual projects. Together, we are driving forward a new form of molecular prevention. We developed this concept within the European LifeTime consortium and described it in the journal “Nature” in 2020. Hundreds of scientists from across Europe were involved, so we are extremely well connected internationally.

With the Berlin excellence cluster ImmunoPreCept, there is a strong complementary focus on immunology. What is new with the Einstein Center is a structured, cross-institutional collaboration to find new paths toward application. Clinicians, basic researchers, and data scientists will work together systematically with their respective expertise, rather than alongside one another.

Major advances arise neither solely in the clinic nor exclusively in the laboratory nor at the computer. The Einstein Center will create a shared platform with clear rules, short paths, and without unnecessary bureaucratic hurdles. This is absolutely essential because complex collaborations otherwise often fail before they even begin.

During the two-year preparatory phase for the Einstein Center, we looked internationally for role models. There is an interesting structure in Lausanne. Then there is the Broad Institute in Boston, where Harvard, MIT, and others have joined forces. In Berlin, we want to gradually create an open network in which the basic rules are defined for everyone interested, making processes faster as a result. By the way, the topic of molecular prevention is also being addressed elsewhere in Germany and internationally.

Is Berlin well positioned to advance this concept?

Leif Erik Sander: We have state-run universities that provide education at a very high level. With Charité, we have the largest university hospital in Europe, as well as a very high density of non-university research institutions where top minds work with the most modern technologies. They contribute the expertise required for such a complex and forward-looking project. For me, this combination is Berlin’s competitive advantage that will quickly result in real added value.

For highly qualified young talent in Berlin, institutional boundaries hardly matter. They have great ideas and want to freely use technologies from different institutions to make new discoveries. That is why they come here. The Einstein Center will provide a structural framework for this. Of course, the next Broad Institute will not emerge here in just a few years. But something that is driven by a similar spirit will: top institutions working together to make a difference. Collaboration is orders of magnitude better than everyone trying on their own and focusing only on themselves. This will also lead to shared value creation.

Over the next six years, we want to initiate the first joint innovations, ranging from new diagnostic approaches to patents and spin-offs. A key milestone will be the formalized collaboration of Berlin’s leading organizations. This will offer a platform for the future from which a great deal of good can emerge, benefiting not only medicine but also Berlin as an innovation hub.

The project is quite ambitious. Where will you start?

Nikolaus Rajewsky: During the preparatory phase, young researchers came together across institutions and jointly defined initial use cases. This bottom-up dynamic is an important part of our concept.

What are these use cases?

Leif Erik Sander: We are initially focusing on two organ systems for which there is a high medical need. One focus is dementias. From a healthcare cost perspective, they are expensive to manage and are extremely burdensome for people affected and their families. In several interdisciplinary projects, we are searching for new approaches to diagnose dementias as early as possible in order to influence disease progression. The second focus is chronic lung diseases, which are also widespread conditions. It is often unclear how they develop. With current therapy, we try to slow their progression. But it would be far better to detect these diseases much earlier and cure them.

In addition, we are investigating how organ systems communicate with one another. Damage in one organ can trigger domino effects elsewhere in the body. Such systemic connections have not been not readily apparent within the disease silos in which we have been working; we are now bringing them together. The first two focus areas will hopefully inspire other researchers to use the Einstein Center platform.

Why should people seek medical care even if they feel healthy?

Nikolaus Rajewsky: Many already do, for example through mammography, dental check-ups, or in the case of known genetic risks. This form of prevention will continue to evolve. It is important to conduct societal debate on the issue of prevention openly and transparently.

Leif Erik Sander: If we want to preserve our health and social systems in Germany with an aging population, prevention is indispensable. Leaving it unaddressed would be one of the greatest strategic mistakes one could make. Oral care is a great example. Dentists hardly ever see truly poor dental health anymore. People go for check-ups and professional cleanings, even though it is not always pleasant and sometimes has to be paid for out of pocket. But it pays off in the long term.

The old saying “there is no glory in prevention” is wrong. Only if we intervene earlier and achieve cures instead of chronic long-term therapies will medical progress remain financially sustainable.

What is needed to bring us closer to this goal?

Leif Erik Sander: There is a lack of sufficient venture capital, as is the case everywhere in Europe. Political and tax frameworks also need to be improved. And we do not yet have a strong culture of commercializing our discoveries. Without these things, knowledge does not reach the patient’s bedside! Discoveries lead to medicines, tests, new devices, and eventually they become part of standard care that is covered by medical insurance. That is how medicine works.

Value creation is also part of the Einstein Center’s mission, because profits can then be reinvested. This will generate more cutting-edge research and ultimately create a highly qualified workforce with and well-paying jobs. Within the Einstein Center, we can demonstrate in a protected setting how joint innovation can succeed. This can serve as a blueprint, because in my view, Berlin still has enormous untapped economic potential in the biotech and life sciences sector.

It is an opportunity …

Nikolaus Rajewsky: I was very positively surprised by the enthusiasm with which top scientists in Berlin were involved from the very beginning. This shows that we struck a nerve.

This city needs new ideas for how we want to generate value in the future. Until World War II, there was a lot of industry here. Then mainly administrative structures followed. In recent years, a great start-up scene has emerged. But where Berlin is truly excellent is in biotech and top-level medicine. This is where value creation that benefits everyone can emerge. We are appealing to policymakers in Berlin and at the federal level to seize this opportunity.

In Boston, a huge ecosystem has developed around the biotech industry that contributes to the prosperity of the entire region. There, policymakers spoke to biologists and asked what they needed. The answer was: framework conditions that allow rapid progress. They implemented them. The Einstein Center is a beginning, and we are very grateful to the foundation for its funding. It is an invitation to consider whether such a vision for the future can make Berlin sustainably attractive.

Interview: Jana Schlütter.

Professor Nikolaus Rajewsky is Director of the Berlin Institute for Medical Systems Biology of the Max Delbrück Center. Professor Leif Erik Sander is Medical Director of the Department of Infectious Diseases and Critical Care Medicine at Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Both are spokespeople for the Einstein Center for Early Disease Interception.

www.mdc-berlin.deResearch, Innovation / 05.01.2026

A spin-off targeting neuromuscular disorders

A team led by Mina Gouti has developed a stem cell-based model that enables researchers to test new drugs to treat neuromuscular diseases and to refine existing therapies. The project, called NMJCare, was named one of the top ten ideas in the national Science4Life start-up competition.

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is one of the most severe genetically inherited neuromuscular disorders, affecting about one in 10,000 children. Despite therapeutic advances in recent years, the condition remains incurable. Researchers continue to rely on reliable, patient-specific models to test new treatments.

Dr. Mina Gouti, head of the Stem Cell Modeling of Development and Disease lab and her team at the Max Delbrück Center have developed just such a model. They have grown structures from patient-derived stem cells that closely mimic the functional interaction between nerve fibers, motor neurons, and muscle fibers in the human body. Dr. Ines Lahmann, a postdoctoral researcher in Gouti’s lab, now plans to transform this scientific innovation into a market-ready product. Her project, NMJCare, has been chosen as one of the ten best submissions out of more than 120 entries in the national Science4Life start-up competition.

The award gives Lahmann access to expert guidance on building a viable business model. NMJCare will also receive support through the GeneNovate Entrepreneurship Program, which offers strategic coaching in company formation, communication, and business planning. “These are all key building blocks for driving targeted technology transfer,” says Lahmann.

One model, many options

NMJCare marks the beginning of a new phase for Lahmann. In addition to scientific questions, her focus is now shifting to topics like patents, target audience analysis, and funding strategies. “Those are things I hardly had to think about before,” Lahmann says. “But now they determine whether our idea can truly become market-ready.” The potential of NMJCare is significant: the model allows high-throughput testing of thousands of potential drug compounds before moving into costly preclinical or clinical trials.

At the same time, the system makes it possible to better understand why patients respond differently to therapies. “That’s a crucial step toward more individualized treatment approaches,” Lahmann explains. Potential users of the model include pharmaceutical companies, academic research groups, and firms in the field of personalized medicine. NMJCare can be flexibly adapted to meet their needs – by selecting specific stem cell lines or investigating short-or long-term drug effects, for example.

“For an idea to become viable, it takes constant exchange – and also critical perspectives from the outside,” says Lahmann. Through the GeneNovate and Science4Life programs, she will be connecting with like-minded peers as well as mentors from business, law, and finance. With their support, she hopes that NMJCare will evolve from a lab-based project into a full-fledged spin-off.

Source: Max Delbrück Center

A spin-off targeting neuromuscular disorders

Research / 19.12.2025

What determines the fate of a T cell?

Researchers at the Max Delbrück Center have found that a cellular housekeeping mechanism called autophagy plays a major role in ensuring that T stem cells undergo normal cell division. The findings, published in “Nature Cell Biology,” could help boost vaccine response in older adults.

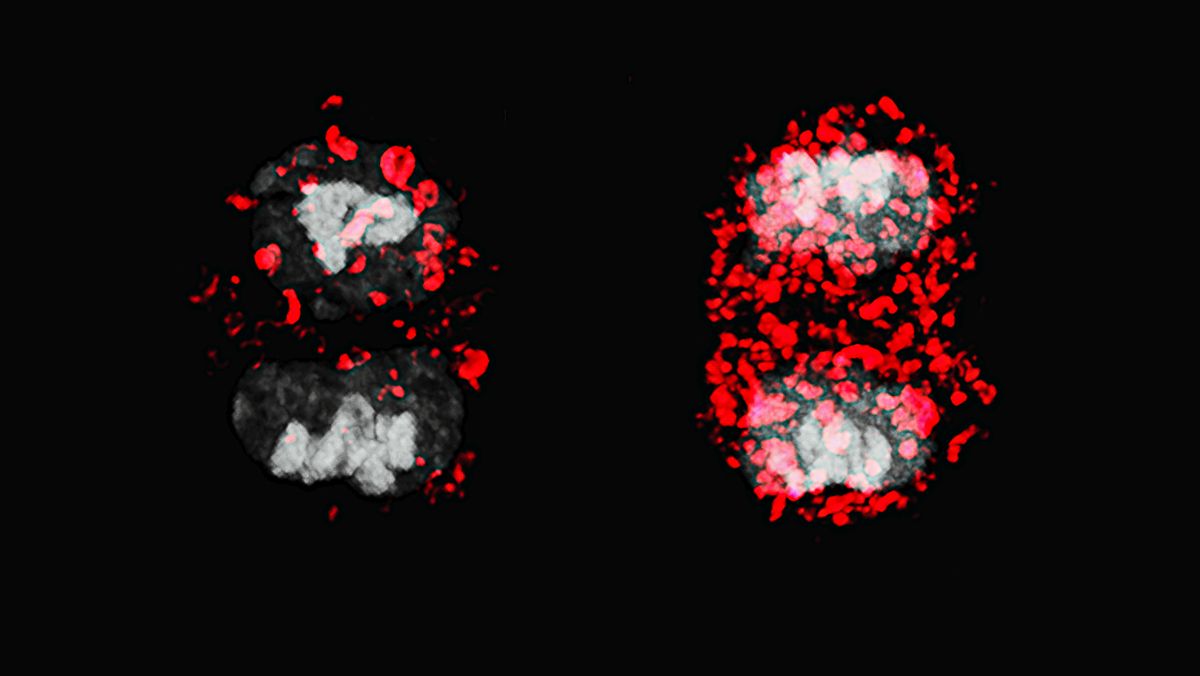

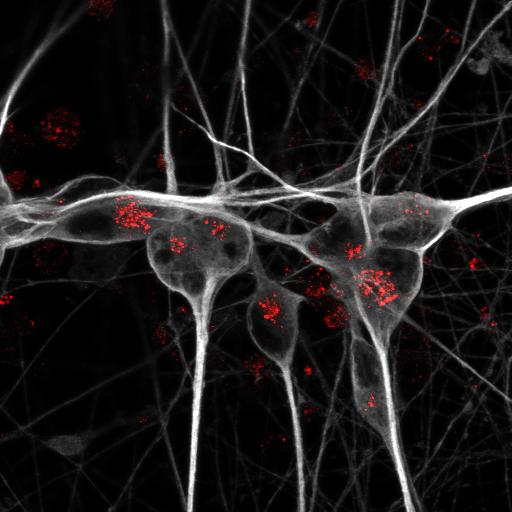

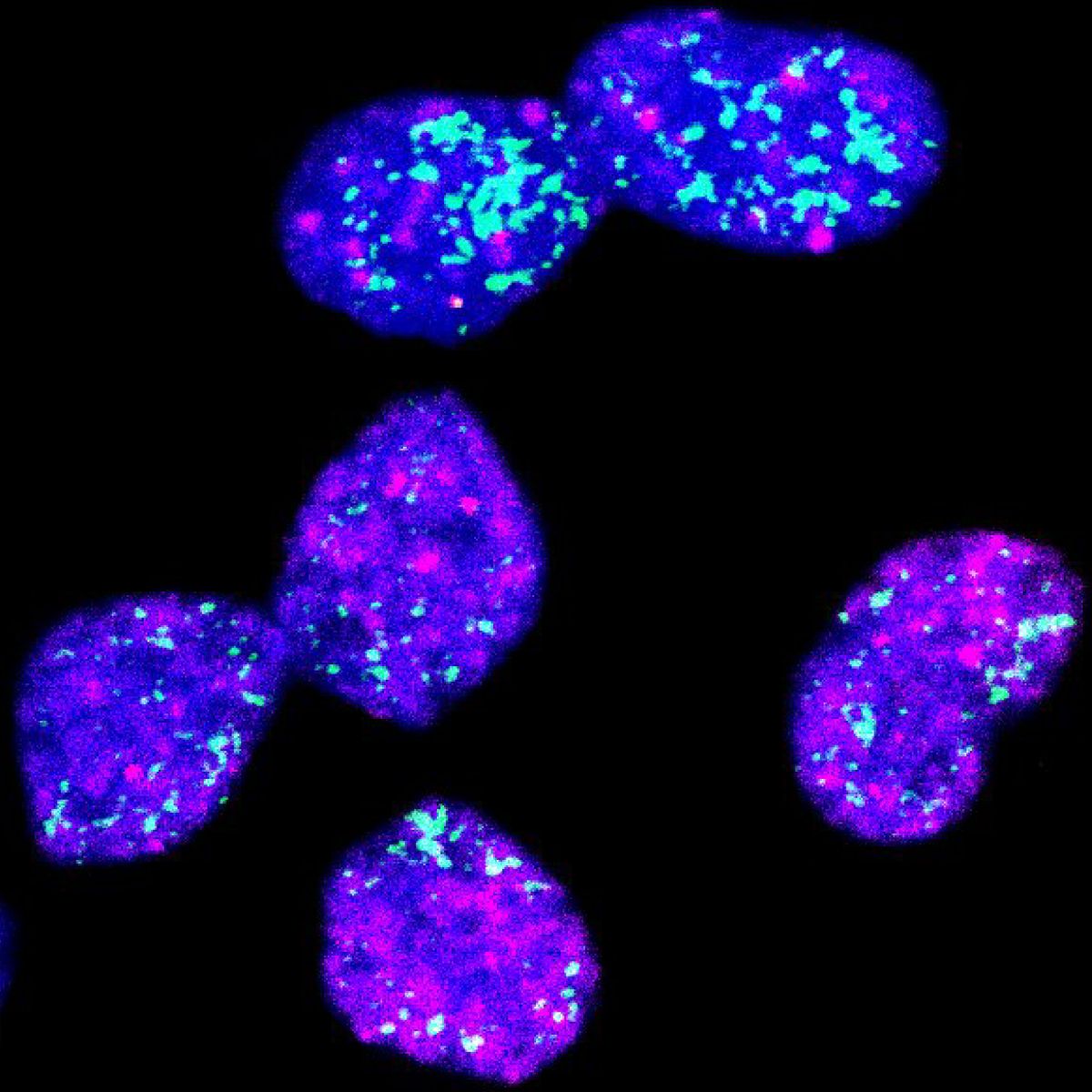

When killer T cells of our immune system divide, they normally undergo asymmetric cell division (ACD): Each daughter cell inherits different cellular components, which drive the cells toward divergent fates – one cell becomes a short-lived fighter called an effector T cell, the other cell becomes a long-lived memory T cell.

Research by Professor Mariana Borsa at the University of Oxford and colleagues in the Cell Biology of Immunity lab of Professor Katja Simon at the Max Delbrück Center has shown for the first time that cellular autophagy – a “housekeeping” mechanism by which cells degrade and recycle cell cargo – plays a critical role in this decision process.

“Our study provides the first causal evidence that autophagy plays a central role in ensuring that T cells go through ACD normally,” says Borsa, first author of the paper who now leads a research group at the University of Basel. “We found that when T stem cells divide, daughter cells inherit different mitochondria, which influences the T-cell’s destiny,” says Borsa. “By understanding this process, we can start to think about ways to intervene to preserve the function of immune memory cells as we age.”

Split personality

To study ACD in greater detail, the researchers used a novel “MitoSnap” mouse model in which they could tag mitochondria sequentially and discriminate between those in mother and daughter cells. T-cells contain many mitochondria. By tracking how old, damaged mitochondria were distributed between daughter cells, they found that in healthy cells, autophagy was crucial in ensuring that one daughter cell was clear of old mitochondria. This inheritance profile sent the cell down the path toward becoming a long-lived memory precursor cell – immune cells that “remember” a pathogen and begin rapidly dividing when the pathogen is encountered again. Meanwhile, the other daughter cell that took on the older mitochondria became a short-lived effector T-cell – a type of immune cell that rapidly divides to fight off immediate threat. These cells die when the threat is cleared.

When autophagy was disrupted, however, this careful sorting broke down. Both daughter cells inherited damaged mitochondria and hence, were destined to become short-lived cells.

“It was surprising to see that autophagy plays a role beyond just cellular housekeeping,” says Borsa. “Our findings suggest asymmetric inheritance of mitochondria as a potential therapeutic target for memory T cell rejuvenation.”

Boosting vaccine response

By boosting autophagy before or during T stem cell division, it may be possible to enhance the generation of memory cells – the backbone of long-term immunity and vaccine effectiveness.

What’s more, the researchers analyzed daughter cells using single-cell transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics and found that effector cells burdened with damaged mitochondria depend heavily on a metabolic pathway called one-carbon metabolism. Targeting this pathway could offer another way to subtly shift the immune balance – nudging T stem-cells toward becoming memory instead of effector cells, Borsa says.

“In the long run, this research could inform strategies to rejuvenate the aging immune system, making vaccines more effective and strengthening protection against infections,” adds Simon. The researchers are planning to further validate their findings in human T-cells.

Photo: T stem cells normally undergo asymmetric cell division (left) whereby one daughter cell becomes a long-lived memory T cell. When autophagy is disrupted, both daughter cells inherit old mitochondria (red) and become effector T-cells. © University of Oxford

Text: Gunjan Sinha

Source: Press Release Max Delbrück Center

https://www.mdc-berlin.de/news/press/what-determines-fate-t-cell

Research / 17.12.2025

Observing synapses in action

A team of Berlin-based researchers led by Jana Kroll and Christian Rosenmund has captured the fleeting moment a nerve cell releases its neurotransmitters into the synaptic cleft. Their microscopic images and description of the process are published in “Nature Communications.”

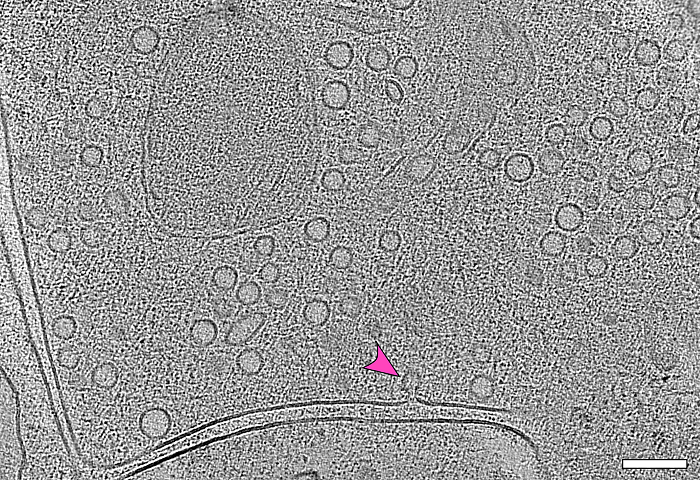

It takes just a few milliseconds: A vesicle, only a few nanometers in size and filled with neurotransmitters, approaches a cell membrane, fuses with it, and releases its chemical messengers into the synaptic cleft – making them available to bind to the next nerve cell. A team led by Professor Christian Rosenmund of Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin has captured this critical moment of brain function in microscopic images. They describe their achievement in the journal “Nature Communications.”

Point-shaped connections

“Until now, no one knew the exact steps of how synaptic vesicles fuse with the cell membrane,” says Dr. Jana Kroll, first author of the study and now a researcher in the Structural Biology of Membrane-Associated Processes lab headed by Professor Oliver Daumke at the Max Delbrück Center. “In our experiments with mouse neurons, we were able to show that initially, the process begins with the formation of a point-shaped connection. This tiny stalk then expands into a pore through which neurotransmitters enter the synaptic cleft,” Kroll explains.

“With technology we developed over five years, it was possible for the first time to observe synapses in action without disrupting them,” adds senior author Professor Christian Rosenmund, Deputy Director of the Institute for Neurophysiology at Charité. “Jana Kroll truly did pioneering work here,” says Rosenmund, who is also a board member of the NeuroCure Cluster of Excellence.

The images were produced at the CFcryo-EM (Core Facility for cryo-Electron Microscopy), a joint technology platform operated by Charité, the Max Delbrück Center, and the Leibniz Research Institute for Molecular Pharmacology (FMP) that is directed by Dr. Christoph Diebolder. Also central to the study were Professor Misha Kudryashev, head of the In Situ Structural Biology lab at the Max Delbrück Center, and Dr. Magdalena Schacherl, Project Leader of the Structural Enzymology group at Charité.

Flash-frozen in ethane

To observe synapses in action, the team used mouse neurons genetically modified through optogenetics so they could be activated by a flash of light – prompting them to secrete neurotransmitters immediately. One to two milliseconds after a light pulse, the researchers flash-froze the neurons in liquid ethane at minus 180°C. “All cellular activity stops instantly with this ‘plunge freezing’ method, allowing us to visualize the structures using electron microscopy,” explains Kroll.

The method revealed another intriguing detail: “We found that most of the fusing vesicles were connected by tiny filaments to at least one other vesicle. As soon as one vesicle fuses with the membrane, the next one is already in position,” Kroll reports. “We believe that this direct form of vesicle recruitment enables neurons to send signals over a longer period of time and thus maintain their communication.”

Toward better epilepsy treatment

The vesicle fusion process visualized by the team takes place millions of times a minute in the human brain. Understanding it in detail has important clinical implications. “In many people with epilepsy or other synaptic disorders, mutations have been found in proteins involved in vesicle fusion,” explains Rosenmund. “If we can clarify the precise role of these proteins, it will be easier to develop targeted therapies for these so-called synaptopathies.”

“The time-resolved cryo-electron microscopy approach using light, as we’ve presented here, isn’t limited to neurons,” Kroll adds. “It can be applied across many areas of structural and cell biology.” She now plans to repeat the experiments at the Max Delbrück Center using human neurons derived from stem cells. That won’t be easy, she notes: “In the lab, it takes about five weeks for the cells to develop their first synapses – and they are extremely fragile.”

Text: Anke Brodmerkel

The image captures the moment during which a vesicle (arrow) fuses with the cell membrane. By superimposing several electron microscopy images – a process known as electron tomography – it is possible to see how many vesicles are waiting at the end of a nerve cell to release their biochemical messengers into the synaptic cleft. This space between two nerve cells can be seen as a double line in the image.

© Jana Kroll, Charité / Max Delbrück Center

Source: Joint press release by Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Max Delbrück Center

Observing synapses in action

Innovation / 13.11.2025

Eckert & Ziegler Achieves Further Earnings Growth and Double-Digit Sales Growth in the Medical Segment

Eckert & Ziegler SE (ISIN DE0005659700, TecDAX) increased sales in the first nine months of 2025 by 4% to €224.1 million compared to the same period last year. EBIT before special items from continuing operations (adjusted EBIT) rose by 9% to €50.8 million. Net profit (from continuing and discontinued operations) grew by 28% to €29.9 million, or €0.48 per share.

In the Medical segment, sales in the first nine months of the year amounted to €119.7 million, up around €15.2 million or 15% on the previous year's level. The business with pharmaceutical radioisotopes remains the most important source of revenue. Particularly noteworthy here are the developments in sales of generators, licensing, and contract manufacturing & development (CDMO).

The Isotope Products segment generated external sales of €104.4 million, down €6.6 million or approximately 6% compared to the first nine months of the previous year. Shifts between product groups toward lower-margin products have become apparent in comparison to the same period last year.

For the current fiscal year 2025, the Executive Board confirms its profit forecast published on March 27, 2025, with sales of approx. €320 million and an adjusted EBIT of approx. €78 million.

The complete quarterly report can be viewed here:https://www.ezag.com/Q32025en

3rd quarter of 2025:

- Sales of €75.3 million (previous year: €70.1 million)

- EBIT before special items of €15.4 million (previous year: €14.2 million)

- Net income of €8.5 million (previous year: €5.3 million)

First 9 months of 2025:

- Sales of €224.1 million (previous year: €215.5 million)

- EBIT before special items of €50.8 million (previous year: €46.7 million)

- Net income of €29.9 million (previous year: €23.4 million)

Forecast for 2025:

- Sales of approx. €320 million (confirmed)

- EBIT before special items of approx. €78 million (confirmed)

About Eckert & Ziegler.

Eckert & Ziegler SE, with more than 1.000 employees, is a leading specialist for isotope-related components in nuclear medicine and radiation therapy. The company offers a broad range of services and products for the radiopharmaceutical industry, from early development work to contract manufacturing and distribution. Eckert & Ziegler shares (ISIN DE0005659700) are listed in the TecDAX index of Deutsche Börse.

Source: Press Release Eckert & Ziegler

Eckert & Ziegler Achieves Further Earnings Growth and Double-Digit Sales Growth in the Medical Segment

Innovation / 07.11.2025

T-knife Therapeutics Presents Preclinical Data on PRAME-Targeted TK-6302 Highlighting its Potential as a Promising, Category-leading Therapy

– Comprehensive TK-6302 data demonstrate preclinical efficacy and safety, supporting clinical readiness, alongside established scalable manufacturing

– TK-6302 Clinical Trial Application planned in Q4 2025 for initiation of the Phase 1 ATLAS trial in 2026

San Francisco, CA and Berlin, Germany – November 7, 2025 - T-knife Therapeutics, Inc., a biopharmaceutical company developing T cell receptor (TCR) engineered T cell therapies (TCR-T) to fight cancer, today announced multiple presentations on TK-6302 were featured at the Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) Annual Meeting. TK-6302 is a differentiated, PRAME-targeted TCR-T that incorporates leading innovations, including a high-affinity TCR, a chimeric CD8 co-receptor that engages CD4 T cells and provides co-stimulation upon TCR engagement, and a FAS checkpoint converter that boosts T cell fitness and survival.

“We have conducted numerous preclinical studies evaluating TK-6302, our supercharged PRAME targeting TCR-T,” stated Peggy Sotiropoulou, Ph.D., Chief Scientific Officer of T-knife. “The competitively differentiated and consistent performance demonstrated across all analyses positions us with confidence as we prepare for the initiation of the ATLAS Phase 1 clinical trial. With the totality of the data, we have demonstrated preclinically that TK-6302 shows best-in-class anti-tumor efficacy and T cell fitness compared to peer company PRAME TCR-T approaches. Additionally, we have established our clinical manufacturing process with scalable production to support clinical development.”

Data Overview

A poster titled “Analysis of PRAME in advanced/metastatic solid tumors shows homogeneous expression and stability between lesions, across treatment lines, and upon exposure to checkpoint inhibitors” (Abstract 27) demonstrated that PRAME is expressed in multiple solid tumors and minimally present in healthy tissues, supporting its potential as a therapeutic target capable of driving deep, durable responses with a low risk of antigen-negative relapse.

A poster titled “TK-6302, a supercharged PRAME TCR-T cell therapy containing a high affinity TCR, a costimulatory CD8 coreceptor and a FAS-based switch receptor, demonstrates preclinical safety and efficacy,” (abstract 329) showcased preclinical studies demonstrating the anti-tumor activity, polyfunctionality, T cell fitness and favorable safety profile of TK-6302. TK-6302’s multi-mechanistic mode of action was further characterized through key observations:

- Supercharged PRAME CD4 and CD8 T cells directly kill tumor cells via the high-affinity TCR and chimeric CD8 co-receptor that engages CD4 T cells and provides co-stimulation upon TCR engagement (co-stim CD8 CoR).

- Supercharged PRAME CD4 T cells secrete cytokines to support CD8 T cell function and trigger global immune responses by recruiting and activating other immune cells, driving tumor control through antigen spreading, beyond HLA and target constraints.

- The co-stim CD8 CoR mediates TCR-T fitness and durable functional activity through optimal co-stimulation.

- The FAS-TNFR checkpoint converter enhances TCR-T cell engraftment and persistence via activation in the lymph nodes and prevention of FAS-L induced cell death in the tumor.

A poster titled “In-depth characterization of TK-6302, a supercharged PRAME TCR-T therapy, manufactured at-scale from healthy donors and patients,” (abstract 347) presented data demonstrating potent anti-tumor activity of TK-6302 across multiple assays, including physiologically relevant 3D tumor models that mimic solid tumor barriers, with high yield manufacturing performance. Additionally, transcriptomic profiling at harvest and following co-culture with cancer cells revealed a TK-6302 gene expression signature consistent with broad immune activation, enhanced tumor homing and sustained T cell fitness.

A poster titled “Preclinical assessment of genome editing safety in CRISPR-engineered PRAME-targeting TK-6302 TCR-T cells demonstrates editing precision and safety,” (abstract 330) reviewed comprehensive analyses of TK-6302 drug products manufactured at-scale with the clinical process, which showed high editing precision with full and correct integration of the transgene, and without concerning off-target or chromosomal aberrations.

Copies of the poster presentations can be found at: https://www.t-knife.com/technology/scientific-publications.

About T-knife Therapeutics

T-knife is a biopharmaceutical company dedicated to developing T cell receptor (TCR) engineered T cell therapies (TCR-Ts) to deliver broad, deep and durable responses to solid tumor cancer patients. The company’s unique approach leverages its proprietary platforms and synthetic biology capabilities to design the next-generation of supercharged TCR-Ts with best-in-class potential.

The company’s lead program, TK-6302, is a supercharged PRAME targeting TCR-T that includes novel enhancements to improve T cell fitness and persistence, to overcome the immunosuppressive tumor micro-environment, and to improve durability of response. The company plans to submit a Clinical Trial Application (CTA) in Q4 2025 and to initiate the ATLAS Phase 1 clinical trial of TK-6302 in 2026.

T-knife was founded by leading T cell and immunology experts utilizing technology developed at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine together with Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, is led by an experienced management team, and is supported by a leading group of international investors, including Andera Partners, EQT Life Sciences, RA Capital Management and Versant Ventures. For additional information, please visit the company’s website at www.t-knife.com.

Research / 21.10.2025

Why APOE4 raises Alzheimer’s risk

Researchers at the Max Delbrück Center and Aarhus University have found a mechanism through which the gene variant APOE4, long linked to a high risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, impairs neuronal function in the aging brain. The research was published in “Nature Metabolism.”

The gene variant APOE4 has long been known as the strongest genetic risk factor for late-onset Alzheimer’s disease, raising the risk about twelve-fold as compared to non-carriers. Yet its close relative, APOE3 – the most common variant in humans – does not appear to increase susceptibility to the disease. The reason for this stark difference has been unclear.

Now, a study published in “Nature Metabolism” may explain the mechanism: Neurons exposed to APOE3 protein can use long-chain fatty acids as an alternative source of energy when glucose is scarce. But this vital metabolic pathway is blocked in the APOE4 brain.

“The ability to use glucose diminishes in the aging brain, forcing nerve cells to use alternative sources for energy production,” explains Professor Thomas Willnow, Group Leader of the Molecular Cardiovascular Research lab at the Max Delbrück Center and senior author of the paper. Willnow also holds a professorship in the Department of Biomedicine at Aarhus University. “APOE4 appears to block nerve cells from utilizing lipids as an alternative energy source when their supply of glucose decreases.”

Experiments in mice and human neurons

The brain consumes around a fifth of the body’s glucose supply. Yet as we age, its ability to metabolize glucose drops. This decline is a hallmark of both normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease, and starts decades before symptoms of dementia become apparent.

ApoE, the protein encoded by the APOE gene, belongs to a family of fat-binding proteins, called apolipoproteins. In the central nervous system, ApoE is mainly released by brain cells called astrocytes. It helps to deliver lipids to nerve cells.

To understand why the APOE4 variant so dramatically raises the risk of Alzheimer’s disease compared to APOE3, co-first authors Dr. Anna Greda, assistant professor at the Willnow lab at Aarhus University, and Dr. Jemila Gomes, who did her PhD in Aarhus and is now a postdoc in the Willnow lab in Berlin, collaborated with the Technology Platforms for Pluripotent Stem Cells and Electron Microscopy at the Max Delbrück Center. They used genetically engineered mice that carry human APOE3 or APOE4 genes. They found that APOE3 interacts with a receptor called sortilin to deliver fatty acids into neurons. By contrast, APOE4 disrupts sortilin’s function, preventing uptake of lipids by neurons.

To confirm the relevance of their findings for human brain health, the scientists then turned to human stem cell-derived neurons and astrocytes carrying different APOE variants. Again, they observed that APOE3 allowed neurons to metabolize long-chain fatty acids, while the presence of APOE4 shut down this ability.

“By using transgenic mouse models and stem-cell-derived human brain cell models, we discovered that the pathway enabling nerve cells to burn lipids for energy production doesn’t work with APOE4, because this APOE variant blocks the receptor on nerve cells required for lipid uptake,” explains Greda.

New treatments for Alzheimer’s

“Our research suggests that the brain is highly dependent on being able to switch from glucose to lipids as we age. It seems that individuals, who are carriers of the APOE4 gene, may be compromised to do so, increasing their risk of nerve cell starvation and death during aging,” Gomes adds. Still, “this work opens new avenues for interventions that could improve lipid-based energy use in APOE4 carriers.”

There are already marketed drugs that specifically target the body’s ability to utilize lipids, Willnow says. Such drugs can now be studied for their potential to treat people with APOE4. As a proof, the researchers showed that treating neurons with the drug bezafibrate restored fatty acid metabolism in APOE4-expressing cells. Of course, such drugs need to be tested in clinical trials, Willnow adds, “but I am hopeful that our research suggests new treatment options for this devasting disease.”

Text: Gunjan Sinha / Vibe Bregendahl Noordeloos, Aarhus University

Research / 17.10.2025

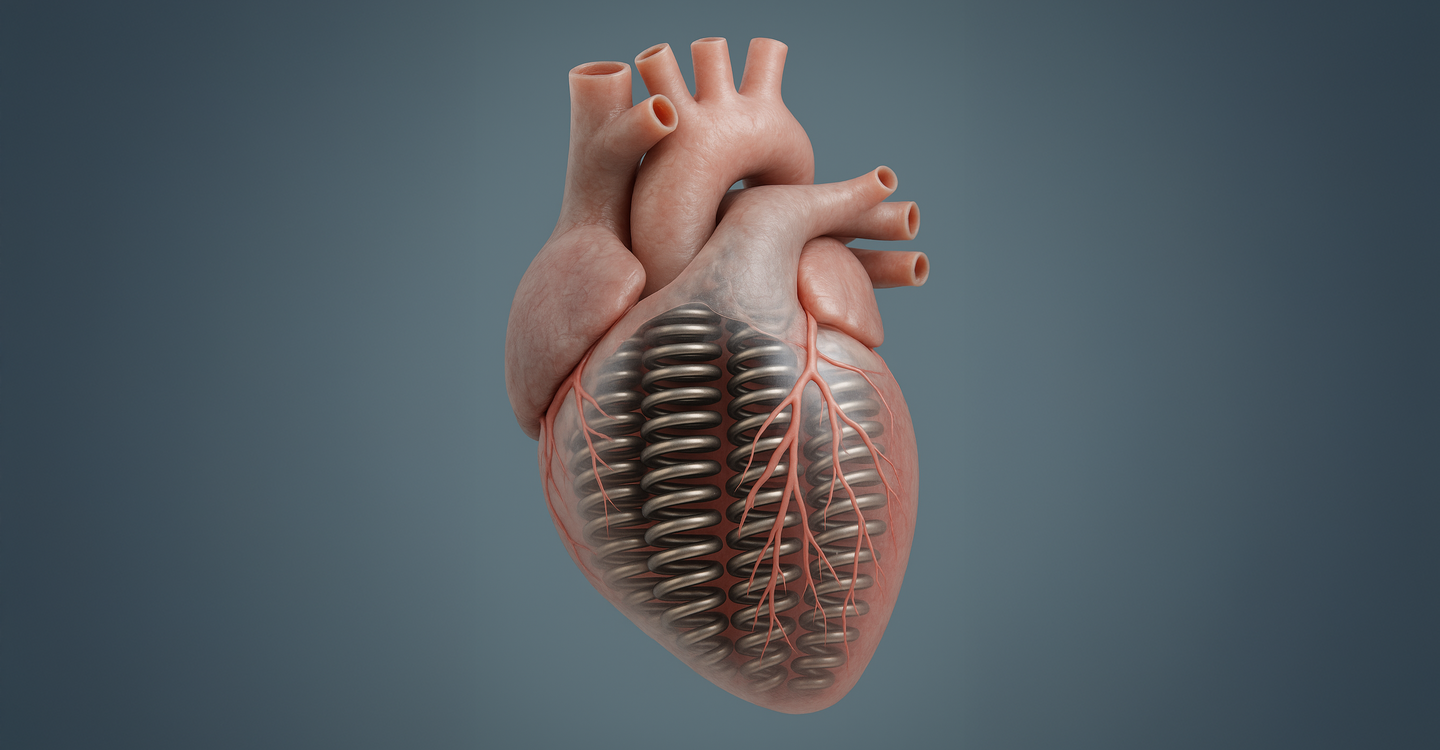

A potential new drug for stiff hearts

Michael Gotthardt at the Max Delbrück Center and collaborators are developing a drug to treat a common type of heart failure characterized by impaired cardiac filling. In “Cardiovascular Research,” his group and a US team showed the therapy improves cardiac function in a mouse model of the disease.

As we age, our muscles tend to stiffen, including one of the most vital muscles in our bodies: the heart. This is why older adults often suffer from a specific type of heart failure whereby the organ continues to pump blood, but becomes too stiff to relax and to fully fill between beats.

“There’s currently no effective medication that lowers mortality in this form of heart failure – heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, or HFpEF,” says Professor Michael Gotthardt, Group Leader of the Translational Cardiology and Functional Genomics lab at the Max Delbrück Center in Berlin. For more than a decade, Gotthardt’s research has focused on uncovering the molecular mechanisms of HFpEF and developing therapeutic strategies to counteract them.

In the journal “Cardiovascular Research,” he and a team led by Professor Henk Granzier from the College of Medicine, Tucson at the University of Arizona – a longtime collaborator – report that a drug they developed, called RBM20-ASO, improves heart muscle elasticity and cardiac filling in a mouse model that better reproduces the multifactorial pathology of human HFpEF than any previously established model. “After treatment with RBM20-ASO, the mice’s hearts were markedly more compliant and capable of expanding and filling with blood after contracting,” Gotthardt explains.

Elastic forms of the protein titin

“Most people with HFpEF have comorbid conditions such as obesity, high blood pressure, elevated blood lipids or high blood sugar,” says Dr. Mei Methawasin, first author of the study who now leads her own group at the University of Missouri at Columbia. “For the first time, we tested the drug in mice that not only developed HFpEF, but also had these comorbidities – to better simulate the human disease.”

The drug is an antisense oligonucleotide (ASO) – a short, single-stranded nucleic acid molecule designed to reduce the amount, and therefore the activity, of the splicing regulator RBM20. This factor plays a critical role in determining whether heart muscle cells produce a more elastic or stiffer version of the giant protein titin, which functions as a molecular spring in cardiac muscle. Gotthardt and colleagues had previously demonstrated that RBM20-ASO prompts heart cells to express more of the elastic titin variant – similar to what’s seen in very young hearts – completely reversing HFpEF-like symptoms in genetic animal models of the disease.

High doses not required

“The current study also aimed to determine the optimal dose of the drug to minimize side effects, including immune system disturbances,” says Methawasin. The team found that reducing RBM20 levels by about half was enough to improve the heart's diastolic function – its ability to fill with blood – without impairing its pumping strength, or systolic function.

“Our treatment significantly reduced left ventricular stiffness and abnormal thickening of the heart muscle, even in the presence of persistent comorbidities,” adds Gotthardt. Moreover, side effects in treated animals were moderate. The researchers believe they can reduce these effects even further by increasing the dosing interval – an approach they plan to test in future studies.

“Our results suggest that using ASOs to modulate RBM20 protein levels could be a viable alternative or complementary therapy for HFpEF – one capable of restoring diastolic function and limiting further organ damage, either as a standalone or adjunctive treatment” says Gotthardt. Supported by the Deutsches Zentrum für Herz-Kreislauf-Forschung and the German Research Foundation, he is planning to bring this treatment to HFpEF patients in collaboration with colleagues from the Deutsches Herzzentrum der Charité in Berlin. Before clinical translation, however, the therapeutic strategy will undergo further evaluation in a porcine model to validate its safety and efficacy.

Text: Anke Brodmerkel

Source: Press Release Max Delbrück Center

A potential new drug for stiff hearts

Research / 23.09.2025

Volker Haucke receives the Ernst Schering Prize 2025

The Ernst Schering Prize 2025, endowed with 50.000 euros, is awarded to Prof. Dr. Volker Haucke, Director at the Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP) and Professor of Molecular Pharmacology at Freie Universität Berlin.This prestigious science award honors his groundbreaking discoveries on the function of signaling lipids, which control the cellular responses to messengers, hormones, and nutrients, thereby shaping central processes in cell communication.

Dysfunctions in lipid signaling are associated with a wide range of diseases—from stroke to neurodegeneration and cancer. Prof. Haucke’s research thus provides critical biomedical insights of far-reaching clinical relevance. From numerous remarkable nominations, an international jury selected him for this award.

At the core of Haucke’s scientific work lies the role of membrane lipids, known as phosphoinositides. Acting as molecular switches, they regulate the transport of messengers and cellular components. His pioneering studies on vesicle transport and neuronal signaling have fundamentally advanced our understanding of cellular communication in the brain.

A systems biology perspective on diseases

Prof. Haucke emphasizes the importance of a systems biology perspective for biomedical progress: “Those who seek biomedical progress must not be content with simple causal chains.” Different diseases may be rooted in the same cellular mechanisms, even if triggered by distinct genes. “If we understand these common mechanisms, drugs that are already approved could prove effective for other diseases as well—faster, more targeted, and with lower risk.” In neuroscience in particular, this approach opens up new perspectives on complex disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and rare genetic diseases.

Beyond theory, Prof. Haucke and his team are also making practical progress. They have developed novel compounds that specifically influence key processes such as cell division and blood clotting. These discoveries open up promising therapeutic options, particularly in the fields of cancer and vascular medicine.

“Through his discoveries, Prof. Volker Haucke has not only revolutionized our understanding of cellular mechanisms, but also paved the way for innovative therapeutic approaches in medicine,” says Prof. Max Löhning, Chairman of the Foundation Council. “He is an outstanding example of how basic research can translate into societal impact.”

New perspectives on the brain

Prof. Dr. Detlev Ganten, Founding Director of the Virchow Foundation and nominator for the prize, highlights one aspect in particular: “Among Volker Haucke’s many important research findinmgs, I am especially fascinated by his findings on the question: What makes the brain a thinking organ? Each of the 100 billion neuronal cells in the human brain has 7,000 points of contact (synapses) to other, far-distant neuronal cells. Volker Haucke has discovered that this extensive synaptic network in the brain is created by signaling lipids that make intelligent, networked thinking possible in the first place.”

The Ernst Schering Prize is awarded annually by the Schering Foundation and honors outstanding scientists worldwide whose groundbreaking research has generated new inspiring models or led to fundamental shifts in biomedical knowledge. Previous laureates include Nobel laureates Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard, David MacMillan, Carolyn Bertozzi, and Svante Pääbo.

Dr. Jörg Maxton-Küchenmeister, Managing Director of the Schering Foundation, emphasizes: “Through his pioneering work on lipid signaling, Prof. Volker Haucke has fundamentally transformed our understanding of key cell processes and opened up new pathways to treating major diseases such as cancer or neurodegenerative disorders. Moreover, his commitment to sustainable lab work deserves special recognition.”